Turning a story into film is a process of achieving a kind of well-temperedness. A blot of words and impressions will not magically copy-paste itself into an action line for a sequence. There is no need to recount the many ways critics and practitioners have discussed this, often to the detriment of both forms.

The only thought I found useful to me was that the movie was never going to be an endgame of the written story—counter to popular and commercial notions of a kind of quantum leap in success when books or stories are adapted to film. Though these notions are valid, not harmful to the art—and in fact aid in increasing the readership and income of the writer—to that same writer, the text must be its own endgame.

The written language of “An Errand,” of course, helped. It is silly to imagine Brenda, the rank-and-file Pinay who is lover to the main character’s boss, saying onscreen: “You know, when you worry too much about something it becomes something else already. Like distrust. Or fear.” It is equally silly to discuss why Filipino writing in English all becomes wersh-wersh to most Filipino movie audiences. Filipino dialogue is not a market discussion. It is part of the authenticity demanded of and by cinema. This is why the question “Who are you writing for?” is hardly asked of Filipino filmmakers—but always of Filipino writers in English.

Early in the adaptation, the problem of the differences in momentums in text and film became very apparent. Small anecdotal tells and circumstantial nuances, which are common material in written fiction, needed to grow into subplots or required explanatory scenes, both of which I have a mental allergy to.

In the end, what was added were not just scenes and not just subplots—there was even a plot-within-a-plot (in the form of a teleserye segment featuring twin sisters, viewed by characters on a smartphone). I discovered that the film story itself demanded an endgame. The film An Errand needed a kind of closure that the short story “An Errand” never needed. Maybe because film is a time-bound medium—everyone in the cinema finishes their consumption of the text at the same time; or maybe because I was an amateur who had seen too many Hollywood movies: thinly veiled cowboy films where comeuppances come up and riders ride into the sunset.

So I made up not just a character, but a cowboy; not just a cowboy, but a made-up one: Rex, a mythical figure from urban legend—a driver who has made his way up to bodyguard.

INT. DRIVER’S LOUNGE

In a nondescript, windowless driver’s lounge, Moroy is hanging out with fellow drivers, among them WILSON, 30, and old MANG BEN, 60. A TV is hanging at an angle on a wall, showing a bad transmission of a local TV game show. Ben is talking as if to no one in particular -- other drivers enter and exit the room randomly, and only Wilson and Moroy seem to be listening to him . . . .

WILSON

Eh di ba na-ambush yun si Bobit?

(Wasn’t that Bobit ambushed?)

BEN

’Di na nga nagpapakita masyado. Yung isa nga dun sa kasama niya, yung pinakabodyguard niya, nadale.

(We don’t see him around much. They got one of his bodyguards.)

Wilson sits up, suddenly interested.

WILSON

Eh yung isa?

(What about the other one?)

BEN

Si Rex.

(Rex.)

Ben’s eyes light up as he prepares to tell a tale.

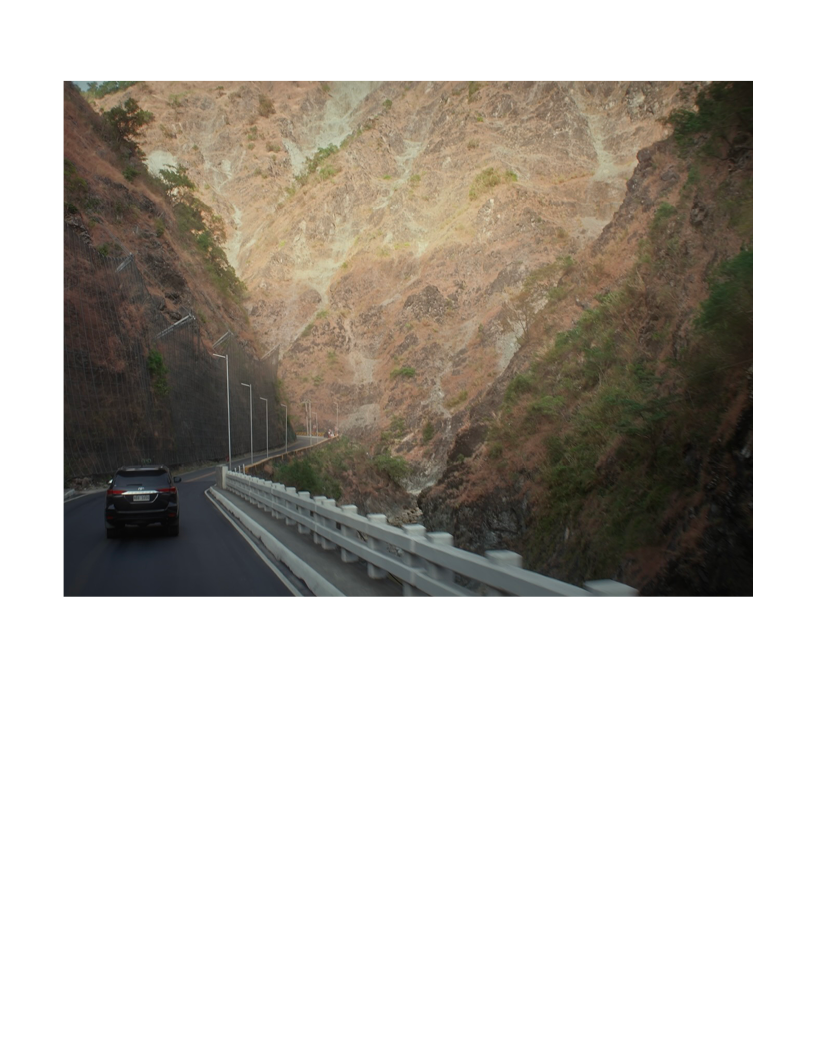

For me, Rex was initially meant to keep the audience in their seats. I felt that the original single story was story enough: at an ungodly hour, driver Moroy is asked by his boss, while they are in Baguio, to fetch the latter’s designer t-shirt and a tin of medicine from his home in Manila and then bring it back up to Baguio—all in a single run. The T-shirt happens to be an old birthday gift from his mistress, with whom he is shacked up at the Baguio Country Club, and the medicine happens to be Viagra, indicating his eagerness to please her. In the end, after a series of micro-rebellions and diversions, Moroy makes good on his errand and delivers his boss’s tin of tablets, leaving the T-shirt in the SUV because he knows it is a decoy for him and his boss’s household, and his boss tips him with one tablet and sends him off.

But the new character makes an appearance at the very start of the movie, written on the spot, as it were, by the aging driver Mang Ben, who first establishes Rex as a real person he has met, but who in the course of his storytelling gradually attributes to him demigod status. It is such a heroic tale that it is immediately both entertaining and suspect, especially to his audience of fellow drivers.

EXT. GRASSY SHOOTING RANGE - DAYA bunch of men are loading pistols, preparing to practice firing them. Among them is REX, the aforementioned driver of the man named “Bobit,” as well as his BODYGUARD, 37. Their TRAINER, 50, is behind them giving them instructions. BEN (V.O.)Si Rex. Naku, eh, kahit drayber lang yun, pinag-weapons training din raw siya. (That Rex. Just a driver but they gave him weapons training.) A bunch of STRAY DOGS are let loose into the grassy area by a CARETAKER. The men start firing at the stray dogs (off-cam). We hear the dogs whimpering as they are shot.Old Ben, suddenly the center of attention, spins his tale further. Rex survives a motorcycle ambush on his boss, the politician Bobit, killing both hitmen in the process. Heavily bleeding from two gunshot wounds, he grabs their bike and rides to the nearest hospital, where he fires his gun into the air to receive attention. INT. SUV - ROAD - DAY Rex is driving while his BODYGUARD COMPANION, 35, rides shotgun with him. BOBIT, in SILHOUETTE, is sitting in the rear. The bodyguard’s radio lets off a sudden squelch, and we hear a burst of radio chatter. RADIO VOICE (O.C.)Alpha, alpha, position na--BOBIT(INTERRUPTING) Patayin mo na nga yan! (Turn that thing off!) BODYGUARD Yessir. The bodyguard dutifully switches off the radio. A SILHOUETTE of two men on a MOTORCYCLE sidles up by Rex’s window.BEN (V.O.)Si Rex, tatlong tama. Sa dibdib. Sa tiyan. Sa hita. (Rex got it three times. They got him in the chest. In the stomach. In the thigh.)Rex took shape first as a sort of cartoon character, an action figure, which then grows in the drivers’ (and I hope, the audience’s) imagination, a sort of living hyperhuman ideal. This process is mirrored in the movie: Rex himself expands in presence and meaning as the film proceeds. It also became peculiar that, especially with the involvement of physical action and bodily injury, a real body with a real presence appeared in this story, a body that changed as the script and my collaboration with my co-producers progressed. Rex suffers two gunshot wounds, realizes his role as a pawn in his own master’s game, and recovers, barely, from his death. He had earned my sympathy as a man in full, no matter how flat he was. (Funnily, even that flatness made me sad for him.)

But that is where the use of my script ends and where the editing begins. Later on, and I should say, completely in the editing room where director Dominic Bekaert had hermetically habituated himself, Rex began to change further. He began to appear as a sort of great, haunting spirit. A shot of Rex walking to the camera and firing a pistol at it, for example, was meant to be sequenced somewhere in the beginning or toward the end of the film, with either placement marking the character’s existence as the driver’s ideal. Instead, in the cut shown at the film’s premiere, Rex flashes in and out, from time to time, in and out of Moroy’s consciousness, mixing with his dreams and visions of his hometown seashore (a tribute to Brocka’s Maynila sa Kuko ng Liwanag)—his image sometimes even superimposed on Moroy himself. So he has become a specter, or a specter in one’s mirror. The only milieu he does not intrude into is the cheap massage parlor, where Moroy’s character, disrobed and in his class element, undergoes a verbal kind of therapy in the hands of Racquel, played by Thea Marabut.

Ultimately, Rex elevates his god status by actually resurrecting himself, hours after the doctors have said it was too late and the death certificate has been signed. In this manner, he erases even his identity, though not his existence. He remembers details that confirm that the ambush was fake, set up by his own boss Bobit, who would do everything in his big small-town power to remove him from the earth.

INT. HOSPITAL CORRIDOR - NIGHT

Top shot of Rex lying in a hospital gurney with a sheet over him.

BEN (V.O.)

Too late na raw. Wala na raw pag-asa. Ginagawan na raw ng death certificate, ganun. Pero akalain mo--

(They said it was too late. There was no hope. They were preparing the death certificate. But what do you know--)

The sheet stirs and slides down over Rex’s face. He suddenly opens his eyes.

In the middle of the night, a heavily bandaged Rex opens his eyes. He tears his IV lines from his arms and struggles out of bed.

BEN (V.O.)(CONT’D)

--biglang nagising si Rex. Nung gabing ’yun, ha!

(Rex wakes up. That very night!)

A wounded Rex struggles out of the hospital gurney. He is in extreme pain, but he manages to stumble through the hallway.

EXT. ROAD - DAY

A bloody REX, his eyes glazed open as if dead, is glassily staring at the camera.

His POV reveals one of Bobit’s “assailants,” revealed by a ripped-open facemask: the TRAINER.

BEN (V.O.)(CONT’D)

Nahinalaan niya agad na yung amo niya mismo ang nagpatira, pinagmukhang ambush lang.

(He figured out that his own boss had set it all up, making it look like an ambush.)

INT. HOSPITAL - LATER

BEN (V.O.)(CONT’D)

Alam niyang ipatutuloy ng amo niya yun pag nalaman niyang buhay pa pala siya . . .

(He knew his boss would go after him if they found out he was still alive . . .)

Rex stumbles through the dark hospital corridors. His wounds begin to bleed again.

Rex clambers out the window.

In retrospect, and with every viewing, I understand why Rex had to be made, for better or for worse. I also understand why, at the risk of possible error in transmission in the theater and terror of encountering confused audiences, Rex needed to make it to some kind of firmer meaning.

But I resisted it, and admitted Rex as someone who could be real or unreal, who could stand for many things. In this manner, Rex himself, the character, and the very idea of him as a created character, had gone beyond being just another body in the movie. He had become a rupture in the narrative, not merely in storytelling terms, but also in cinematic terms.

EXT. NONDESCRIPT ROAD

Moroy is driving on a long road. He sees a man walking on the shoulder in the distance. Moroy speeds up to the man.

We discover that the man is REX, bloodied from his ambush wounds.

Moroy stops the car. Rex grunts and struggles into the passenger seat and pulls the door shut.

The Land Cruiser screeches away.

INT. LAND CRUISER - CONTINUOUS

Rex opens the glove box. Inside is a WHITE ENVELOPE bursting with MONEY. Moroy and Rex exchange a quick conspiratorial look. Moroy is proud to be his getaway driver. He drives on.

In the last scene of the script, above, the appearance of the money added another dimension, and Moroy’s being “proud to be his getaway driver” would have deflated some layers of interpretation. However, in the final edit, as Bekaert directed it and as actor Sid Lucero interpreted it, Moroy freezes, his face held in the kind of blankness that very few actors can achieve like Lucero does. (“I don’t act,” Lucero confessed to me, in all sincerity and authority, on the night before the first day of our shoot.)

In the audiovisual aspect, Rex provided an added layer of literal storytelling as well. The tall tale told by Mang Ben created a parallel chronological timeline that kept the non-linearity of the main story in check, but also created an opportunity for the film to layer on a comment on the power of storytelling, which was something the original short story does not touch on, but simply acknowledges by its form.

At the same time, completely cinematic elements—for example, the discovery of a scar on Moroy’s shoulder by the masseuse Racquel which he matter-of-factly declares is the result of a bullet wound—blurred the lines of questioning.

In written fiction, blurred lines and vague sleights are more welcome and more forgivable than in cinema, where the existence of visuals, down to the location of bullet holes, provides an additional space for interpretation and meaning, and therefore demands deliberate decisions of the filmmaker.

The text has long been published and the movie cut, screened, and packaged for distribution. In reviewing each as a version of the other, as an exercise, one may argue that the existence of Rex, in the movie crudely drawn from myths and magical thinking passed along in drivers’ quarters and waiting rooms, is nothing more than a plot device. The audiovisual story did not need any further plot—or more precisely, plottiness, that fussy bugbear of screenwriting.

But today I feel for Rex, who has grown into something strange and compelling, beyond the endearing, enigmatic McGuffin that he was originally designed to be—an entertainment more interesting and gripping than TikTok reels, TV shows, and tsismis shared among drivers, kept hidden from their masters.

Rex had become a refractive prism through which the middle-class audience could understand their underlings’ and their own dreams more fully and take part in the shared pathos. He had become a visual portal through which Moroy could drive his precarity and empty utility—and see his fool’s errand turn into something real, whatever that reality might be.

.png)