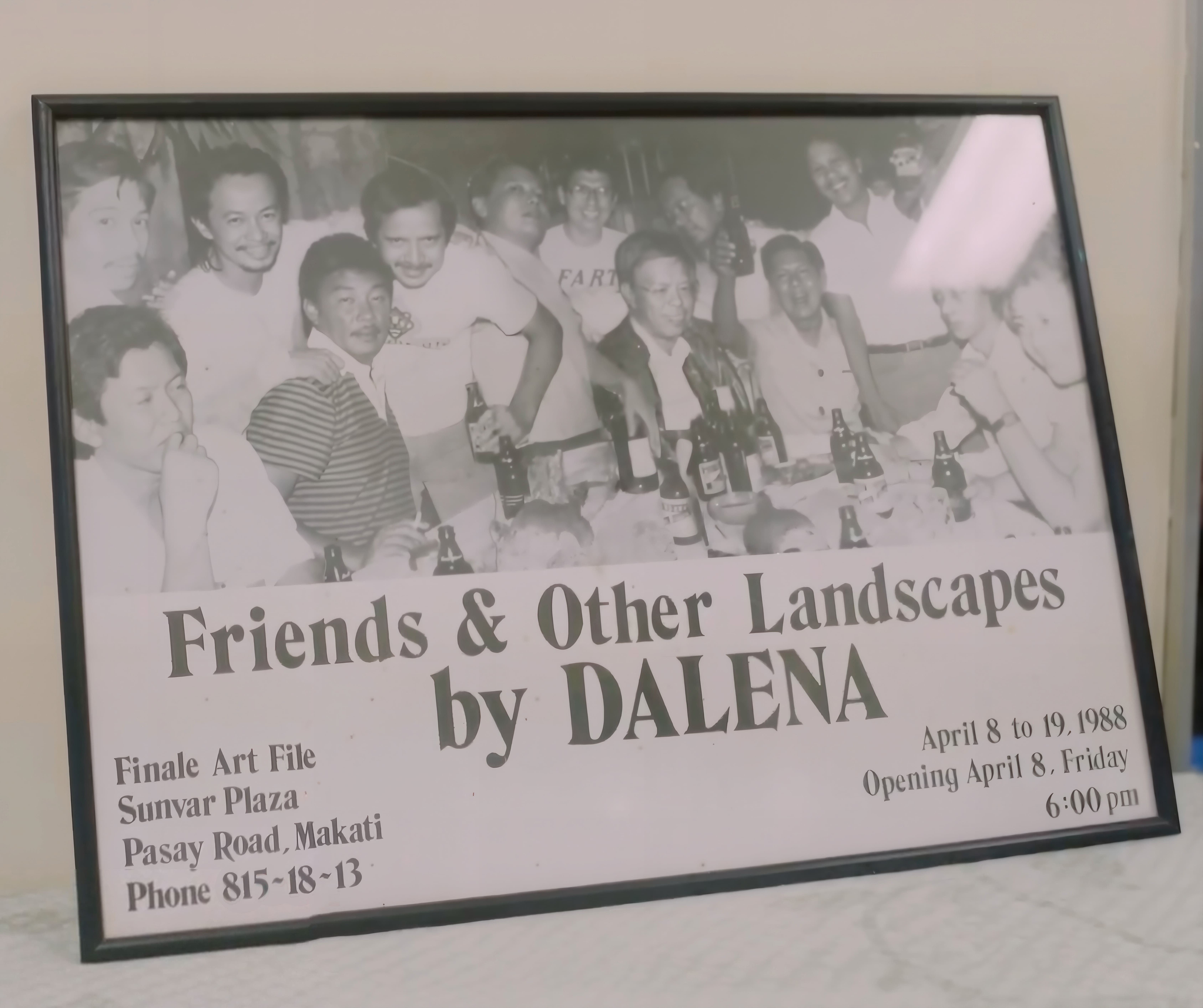

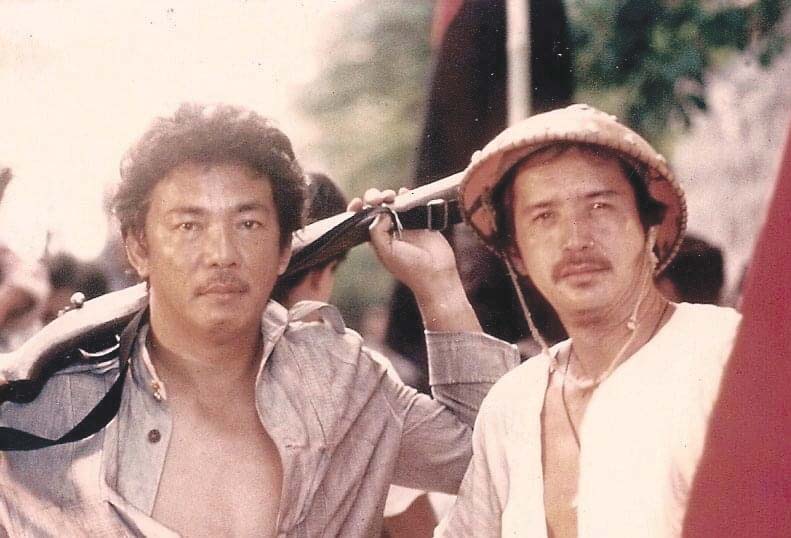

Erwin E. Castillo, author of The Firewalkers, sat down with Nicole CuUnjieng Aboitiz, the academic advisor and journal editor of Exploding Galaxies. Castillo shares with us his time at the Philippines Free Press, his long-time friendships with writers and artists–among them Wilfrido D. Nolledo and Danilo Dalena–and his encounters with real-life monsters.

(Photos by JL Javier)

-

EEC: Erwin E. Castillo

NCA: Nicole CuUnjieng Aboitiz

-

NCA: I wanted to ask you something about the Philippines Free Press… You wrote that ‘these writers sprouted like a cycle of cicadas from all over the regions and the tribes. Mostly educated from an American-modeled common reader, the bright-eyed swarm grew into understanding amid a communications explosion sparked by wartime interests and technologies. Then sheer exhaustion and idealist obligations allowed the release of fledging democracies into a new international order.’ Can you talk to us about that moment in time, that order, in terms of the world of Philippine letters? What did Free Press allow?

EEC: That was a wonderful thing that is long gone and will never return. And I think that that’s a problem for you young people. The Free Press managed to become the national newspaper. I don’t know how they did it. They had the best writers, and they had wonderful people running the show.

American interest, by the way, and of course that was McCulloch Dick [Robert McCulloch Dick] and I forget the name of the other person. They were teachers, American teachers, and they established this newspaper and later Mr. Locsin [Teodoro Montelibano Locsin/Teodoro Locsin Sr.] who was an intellectual and teacher from the South, joined them. And they gathered, after the war, perhaps the best writers that ever [we had]... Of course their prize was to get the young Nick Joaquin. I met Nick when he was only forty-six, only forty-six years old. I was fifteen.

Already by then, many young people were writing for Free Press and writing stories. Mr. Locsin was a writer of fiction—a good enough writer of fiction. He wrote a novel about Rizal, which I have somewhere here. Very bright person, very kind person, very knowledgeable person…It became an organ for everybody. Literally for everybody. Mindanao, the real thing, the real thing. So that when I published a story of mine in the 1960s, a story called ‘Ireland,’ and I went to Dumaguete one summer and met at least three little children named Ireland. What a strange thing! That was Dumaguete—so far away, you know? Because we knew each other. We knew each other. I knew the writers from Mindanao, and of course, the Ilocanos and everybody. We were a community. We were a community that the Free Press made.

EEC: And therefore, and this was the political, sociopolitical thing, but also because it carried a beautiful literary page, the stories of everybody else, which meant that I was reading all sorts of people, all sorts of people, especially when it came for our turn came to write. Then I was meeting strange people from strange places, people young as I am who were already—Jesus, I forget his name—captain of a boat sailing to Singapore. He was sixteen years old, captaining a boat.

And of course I met the Visayan writers, Father Rudy, Renato Madrid, who was a prize winner. He was a priest and a musician—an excellent musician and a drinker. And he would spend time with the Archbishop, he was secretary to the Archbishop, and he was a very nice guy. He died just a few years ago.

And so the Visayan writers, the Mindanao writers—Enriquez and everybody—the Negros families were bringing out heiresses who were writers of genuine talent. Elsa Coscolluela, for example, you know. And it was such a wonderful thing. It was such a wonderful thing that I was very glad to be, well, I was just outside of the magic circle. I was looking in, but I felt that I was part of it.

NCA: So it gave the community a focal point.

EEC: Yes, yes, the Free Press, you know. And therefore the prizes—and this is what you don’t have anymore—a forum for you to compare each other’s work on a weekly basis, where you are able to see, oh this is what she’s doing, oh this is what he’s doing, I’m better than you, etc., etc., and things like that. But there were only fifty-four issues, and therefore fifty-four stories a year, so we were all competing for that space. And the top places, of course, were taken up by Nolledo and Brillantes, so what could we do? But they gave us a turn. They gave us a turn and that was that. With Nick’s encouragement.

NCA: What do you remember of Nolledo? Of course, he’s one of our authors as well.

EEC: Yes. Ding was a lifelong friend. An idol. He invented the language, an English language that’s unmatched anywhere in the English writing world. He was theatrical in the extreme. He was like me, an ugly man. But we strutted around like we weren’t. He was a small, slight man, but he smoked a cigarette and he acted like he was a tough guy.

EEC: He lived in a house, by choice, in an address in Tondo. The street was Makata [Makata St, Sta. Cruz, Manila]. A poet. He paid extra for the apartment because it was on that street. And of course he was dearly in love with Blanca, the wife. They had no children. They adopted a child before they found out that they could have one. He was an excellent, excellent friend. He died young, relatively young. He came back here in triumph, he was making movies, etc. But nothing quite worked out the way that we wanted it to. I appeared in one of his movies. We were all appearing in his movies. We were always trying to do things. Of course he had international success. He founded and edited a rather prestigious magazine called The Iowa Review [Nolledo was the founding fiction editor]. He rediscovered Ralph Ellison, [writer of] the Invisible Man.

When I went [to the University of Iowa], the faculty had been so downgraded that the teacher that I got was, I forgot, an American novelist who wrote The Man Who Looked Like Kennedy [Vance Bourjaily] and it was not very interesting. But Ding had Coover and Donoso.

NCA: So Iowa wasn’t very formative for you?

EEC: I was badly educated at the University of the Philippines. Not the university’s fault. We spent all our time doing other things so we came out of there not knowing anything. Really not knowing anything. We had a special class. And the only person in that class who made money was Jejomar Binay. The poet Willie Sanchez was selling encyclopedias.

So, we could not make money, we could not figure out what we were going to do with our lives…We had to earn livings, but it was Iowa that took me away and gave me a chance to be educated, I think. I read everything. I read everything there or reread everything—things that I should have read and things that interested me. Mainly tales of exploration, the Hackett collection of English things, but really also translations from other travelers. And then I read the Victorians, which was an amazing, amazing thing. The Victorians of that time, well, of course it started with The Golden Bough and they were discovering these ancient oriental things [Referring to James George Frazer's compilation. Original text can be read here] and I was discovering it with them. Of course, I also discovered Pinochet [Augusto Pinochet] around that time so it was the past and the present. Otherwise, otherwise, almost total ignoramus.

NCA: If I could ask you about The Firewalkers and ‘The Watch of La Diane’ specifically and their relationship to one another. In your author’s note in 1992, you wrote that ‘twenty-plus years apart in the writing the two have an obvious warts-and-all family resemblance and a concern for monsters, which may comment on the slowness of my personal progress.’ What are those monsters that you think that they’re concerned with and what do you see is the relationship between the two pieces?

EEC: When I was young I did not believe in evil. I mean I was a late, late gun to learn this. In Iowa, I read a whole sheaf of survivor memories from the Holocaust and of course that was a terrible, terrible thing and I did not know how terrible. I knew the summaries, I knew Anne Frank, I knew all of those things. But these were survivor stories talking about the horror, the horror, the horror. And suddenly I started thinking maybe there is such a thing. Then what happened was that I came face to face with evil here.

I thought that we could make friends. That Filipinos could always be friends—that was our reputation. You give us some food, you give us some liquor, then we are brothers. But such kinship, for certain reasons, was so quickly forsaken. Which means the person who was your brother, who you drank with, etc., for certain rewards, is going to kill you. Is going to kill you, kill you, kill you.

And of course, over and over again, since The Firewalkers, I’ve seen this. The pinnacle may have been the Duterte years, but this was going on then, too. I saw friends murdered by friends and suddenly it was a reality. We buried people that I have known since they were children.

The younger brother of the poet Jose M. Lansang, Jun Lansang, I forget his first name [Lorenzo, see here] but his name was called Utnik, after Sputnik, you know—the Lansang family is a communist family. So, the little boy that I knew, whose portrait I drew when he was a child, he went to the mountain and they killed him. They killed him. And since there were no photographs existing and the body was decomposed, they put my little portrait of him, drawn when he was a little boy, and I thought, Jesus Christ, what are they doing? Why are they doing this? I was seeing corpses almost on a daily basis.

NCA: You said in Esquire that you increasingly felt the irrelevance of fiction to reality. Do you think that’s still true?

EEC: That is not true. Fiction is relevant, of course, but as an amulet. Almost everybody who writes, I think, must believe that writing is amuletic, that it will do something. We go on because we believe. Hemingway wrote that his children were drowned at sea, and I know why he did it: so that his children would not die at sea. I mean, of course, it is superstition to believe that, and we should be cynics, but such faith in the thing persists.

-

This is an edited transcript of an interview done on August 8, 2025 at the Castillo home. Special thanks to the Castillo family.

Exploding Galaxies published the 2025 edition of Erwin E. Castillo’s The Firewalkers. You can get a copy of the book here.